Making the best of the new EU Social Climate Fund

Executive summary

The slow pace of decarbonisation of buildings and transportation threatens the European Union’s goal of reducing emissions by 55 percent by 2030 and achieving net zero by 2050. To address this, a new emissions trading system, ETS2, is being introduced to put a carbon price on fuels used in buildings and road transport. However, the resulting cost increases risk a disproportionate impact on vulnerable households and small and medium sized enterprises.

The European Union has created the Social Climate Fund (SCF) to address these distributional challenges. This instrument redistributes a portion of auction revenues generated by the ETS2 among EU countries, in order to protect the most vulnerable. A much larger share of ETS2 revenues will flow directly to national governments, offering significant opportunities for social measures and investments in the green transition. The use of those revenues will dictate how successful EU countries are in managing the transition and protecting households, particularly in higher-income member states, which will receive relatively smaller shares of SCF funding.

ETS2 is an essential part of the EU climate policy toolkit. Governments should employ good practices, as identified by the European Commission, to tackle emissions from buildings and transport and to gradually phase out income support, in line with the achievement of investment targets and milestones. Higher-income EU countries should develop additional targeted financing levers to protect the vulnerable and to introduce extra enablers to encourage private investment.

Proper sequencing, outreach and communication will be essential to ensure the uptake of measures and public support for policy instruments. Cross-country learning should be leveraged, including through the creation of a European policy registry that will help countries compare their approaches and potentially amend their SCF spending plans on the basis of learning from policies that been successful elsewhere.

Financial support from Allianz Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

1 Introduction

Decarbonisation of buildings and transport needs to be accelerated sharply across the continent if the European Union is to have a realistic chance of achieving its 2030 and 2050 climate targets. Transport accounts for about one quarter of the EU’s emissions, of which 72 percent stems from road transport, with levels rising between 2013 and 2022 1 . Under current policy, annual emissions will only revert to 1990 levels in 2032 2 . Meanwhile, emissions from electricity use, cooling and heating in buildings make up 27 percent of the EU’s total emissions. Though the buildings sector has decarbonised to some extent, the 29 percent reduction in building stock emissions achieved by 2022 relative to 2005 falls significantly short of the necessary level of decarbonisation to be on trajectory to achieve the 2030 climate target (Keliauskaitė et al, 2024).

The start in 2027 of a new emissions trading system covering buildings and transport, the so-called ETS2, will therefore be pivotal to reaching decarbonisation targets. The ETS2 will ensure greater predictability of the EU’s emissions by establishing a clear pathway for the annual reduction of emission allowances. It will also facilitate better fiscal planning, drawing on revenue projections based on the planned reduction of allowances in circulation.

The ETS2 should also complement the Clean Industrial Deal – the EU plan to make decarbonisation an industrial opportunity 3 – by supporting a decarbonised electric-vehicle ecosystem and accelerating charging infrastructure, boosting demand and innovation in Europe’s pressured automotive industry (Menner et al, 2025). Similarly, expanding the heat-pump sector could enhance competitiveness and job retention, while the role ETS2 could play in driving low-carbon heating adoption will be crucial to closing the supply-demand gap 4 .

However, though the trading and reporting of ETS2 emission allowances will be the responsibility of suppliers (ie fossil-fuel companies), the carbon price is expected to be largely passed on to consumers, translating into higher heating bills or fuel costs (Strambo et al, 2022). This raises concerns about the impact on low-income households and small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), which are likely to be burdened disproportionately. In public discourse the potential upside of ETS2 is overshadowed by concern over political backlash and its potential to aggravate energy and transport poverty 5 .

To address these distributional concerns, some ETS2 auctioning revenues will be redistributed, including through the establishment of a Social Climate Fund (SCF), which will pool €65 billion from total ETS2 revenues 6 . This fund is intended to address within-country inequality by supporting the most vulnerable households and SMEs, and to address between-country inequality by helping the most-affected countries more.

The main challenge in this for policymakers is to direct the funds effectively to vulnerable groups. Evidence from the energy crisis showed that many countries worldwide struggled to effectively target households with necessary support because of limited administrative capacity at national level (Castle et al, 2023). This problem has not been sufficiently addressed, creating a risk that scarce financial resources will be used to support or even overcompensate consumers that do not strictly need support. Furthermore, Social Climate Plans, the national documents that detail the use of the SCF, must be submitted by the end of June 2025, suggesting that guidance from the Commission on the drafting of these plans is urgently needed.

2 Managing the distributional effects of climate policy

2.1 Distributional effects of climate policy

While carbon pricing is typically the most efficient decarbonisation policy (Duma et al, 2022), it may have regressive effects, meaning it puts a higher relative burden on lower-income households. This applies to pricing levied directly on households and to indirect taxation through which industry passes costs on to consumers (Wier et al, 2005). Regressivity can stem from multiple channels and is one of the main concerns when designing policies.

Low-income households tend to focus on immediate consumption, experience higher borrowing constraints and spend larger shares of their incomes on essential goods such as heating or food. This leads to higher shares of their incomes spent on products that may be subject to carbon pricing. Households that are unable to invest in green technologies, such as electric vehicles or more efficient heating systems, also see fewer benefits from subsidies provided for such purchases. Emission standards can lead to higher costs for consumers, impacting lower-income households more intensely (Zachmann et al, 2018). Inequality directly affects the welfare and economic growth of countries and hence climate policies should not aggravate inequality (Mejino-López and Zachmann, 2024).

Impacts on income are also unequal. Jobs in carbon-intensive industries are primarily done by lower-income groups (Strambo et al, 2022) and shifts caused by the green transition, such as the move towards electric vehicle production, are already affecting employees 7 . Pisani-Ferry and Mahfouz (2023) stressed that the transition will create and destroy jobs unevenly across sectors. Achieving a net benefit will require successful and effective government measures to reallocate resources and labour.

Differences in the characteristics and circumstances of the most affected individuals and companies are significant between and within EU countries. The drafting of national Social Climate Plans and spending of ETS2 revenues should factor in these differences.

2.2 Buildings

Retrofitting the worst-performing buildings offers immense potential for energy and emissions savings. Deep renovations 8 of just 10 percent of the worst-performing buildings could reduce buildings-related emissions by 20 percent and ETS2 emissions by 8 percent (Keliauskaitė et al, 2024). Renovations of these buildings, often inhabited by low-income households that spend up to 30 percent of their income on heating, could alleviate energy poverty, which affects 50 million Europeans and incurs annual public health costs of €167 billion (Ahrendt et al, 2016).

However, transitioning from coal, oil or gas heating to zero-carbon electric alternatives or connecting to district heating requires substantial financial resources which energy-poor households typically do not have. Moreover, tenants in rented property lack the authority to upgrade their heating systems, leaving them unable to reduce their emissions structurally. As a result, they remain locked into carbon-intensive options, facing rising carbon prices without viable alternatives. Without targeted support to ease the transition, decarbonisation efforts risk being stalled, while vulnerable households face increased financial strain.

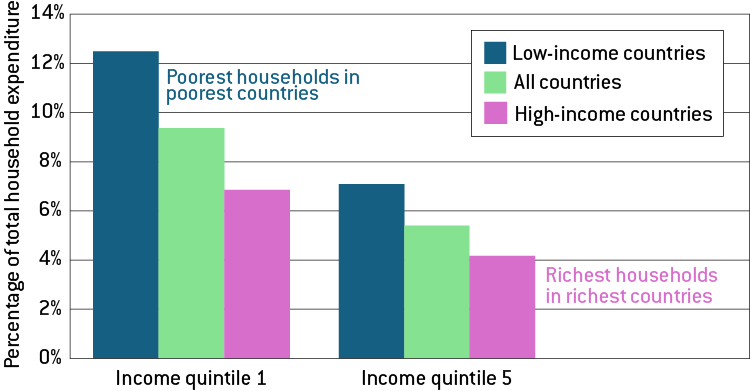

Figure 1: Household expenditure on heating energy (electricity, gas, liquid/solid heating fuels, heat energy), by income quintile

Source: Bruegel based on Eurostat. Note: high-income countries have a net equivalent income of 120-175% of the EU average, low-income countries have a equivalent income of 40-70% of the EU average. Data is missing for Italy.

Data on household expenditure on heating energy reveals that in the lowest-income households in low-income countries, more than 10 percent of expenditure goes on heating (Figure 1). A carbon tax levied on top of (some of) these fuels would impose a large burden on these households. Figure 1, based on Eurostat data, also suggests significant inequality between countries. The households with the highest incomes in low-income countries spend higher shares of their incomes on heating energy than the households with the lowest incomes in rich countries. This is influenced by divergence in incomes across countries and in the quality of buildings, resulting from the materials used in construction or age of the building stock (Gevorgian et al, 2021). Finally, household needs and absolute spending vary widely, so a household may face energy poverty even if it spends relatively more on energy.

The volume of emissions produced by buildings varies greatly across EU countries. It is determined mainly by the energy mix used for heating and the climatic conditions driving heating demand throughout the year (Eden et al, 2023).

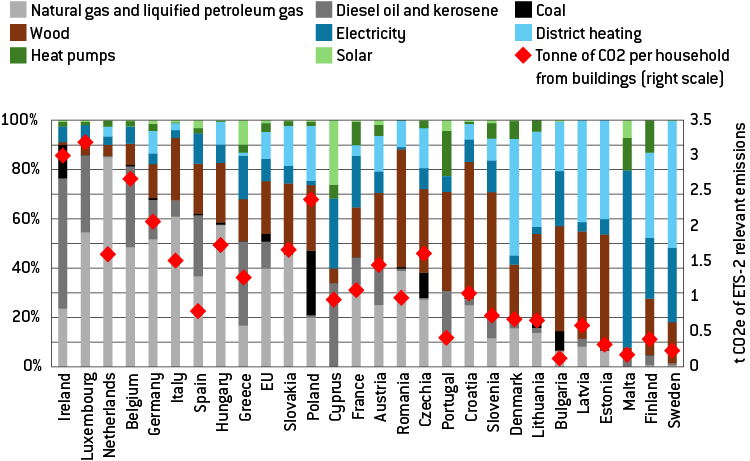

Figure 2: Heating mix of EU countries and emissions per households from ETS2-covered heating commodities

Source: Bruegel based on Eurostat. Note: for Sweden, heat pumps are categorised under electricity.

Countries in which households rely on burning fossil fuels, such as Ireland, generally produce higher per-household emissions than countries that rely on district or electric heating, such as Sweden. Oil and coal, which emit much larger quantities of CO2 per unit of heat generated than natural gas, are drivers behind especially high per-household emissions in Poland and Czechia, despite the total share of fossil fuels in their respective energy mixes being lower than in other countries.

After the introduction of the ETS2, fuel prices will rise as producers pass their cost increases on to consumers. Keliauskaite et al (2024) estimated price fluctuations between €60 and €200 per tonne of CO2, depending on the success of decarbonisation efforts. At an ETS2 price of €60 9 per tonne of CO2, standard use of a gas boiler would incur additional heating costs of €162 per year, whereas users of a coal-boiler would see their costs increase by €350 per year 10 . A German low-income household, where gas is likely used, can thus expect to spend an additional 1.2 percent of its total expenditure on heating because of the ETS2. In Poland, where coal burning is more common, the additional burden for a low-income household relying on coal would be about 3.1 percent. Naturally, with rising carbon prices, the price effect increases proportionately. A price of €200 per tonne of CO2 would have price effects exceeding those of the 2022 energy crisis (Keliauskaite et al, 2024).

2.3 Private and public transport

Lower-income households are also affected by the rising costs of petrol and diesel. About 70 percent of national transport emissions across the EU arise from traffic in areas outside the major cities 11 , suggesting that the rural population will be more strongly affected by the ETS2 fuel price increase, and also that the most significant emission reductions can be achieved through low-carbon investment in these areas.

Typically, transport-poor households are located rurally, especially in lower-income countries (Strambo et al, 2022) 12 . Remotely located households rely more on personal transport because they are further from essential services and lack public transport infrastructure. This already exposes them to a greater financial burden from transport, further aggravated by the ETS2.

The passing-on of costs to consumers could lead to prices rising by up to €0.38 per litre of petrol (Agora Energiewende and Agora Verkehrswende, 2023). However, this represents the worst-case scenario, if prices were to reach €200 per tonne of CO2. In more moderate scenarios, the additional cost would be on average between 0.2 percent to 0.6 percent of consumption expenditure across different income groups of EU households. In contrast to buildings, the largest relative expenditure increases are expected for the higher quintiles of low- and middle-income countries, because of the higher levels of internal combustion engine car usage by those households (Held et al, 2022).

However, using the average across income quantiles means obscuring the divide between rural and urban populations. Figures 3 and 4 detail the differences in this regard and show the absolute and relative costs for Denmark, Germany, Poland and Romania. Based on the differences in driving patterns and incomes across different spatial allocations, the share of income spent on the fuel price increase differs significantly. Rural households in Germany for example are assumed to drive the furthest, leading to the highest CO2 cost. Relative to their incomes, however, rural households in Poland and Romania still spent twice as much as German rural households.

Figure 3: Potential rural and urban increases in fuel costs from ETS2 per year

Figure 4: Potential rural and urban increase in fuel costs from ETS2 as percentage of income

Source: Bruegel. Note: costs estimated using €60 per tonne of CO2 emitted and urban and rural incomes from Eurostat. Urban emissions estimated using average urban car travel kilometres per country according to Eurostat (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Pass…), assuming an average petrol car emitting 170g CO2 per km. Calculation based on the assumption that urban emissions represent 30 percent and rural emissions represent 70 percent of total transport emissions.

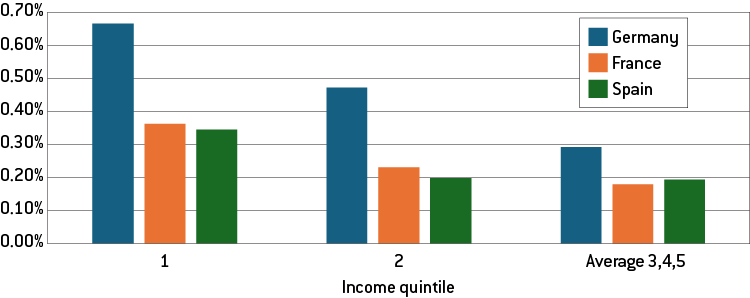

Urban transport in Europe is also dominated by car usage. In most European cities, more than 60 percent of distance covered is travelled by car (as passenger or driver). Increasing fuel prices could encourage the move from cars to public transport, especially for households that have suitable infrastructure available to them, and for whom the switch to electric vehicles remains too costly. An increasing influx of cheap Chinese electric vehicles might alleviate this concern to some extent, but mainly for those already looking to purchase a new vehicle. The problem will remain significant for households that cannot afford the upfront cost and rely on the cars they already own. Figure 5 shows household expenditure on bus transport in different countries, comparing first and second income quintiles to the average of the third, fourth and fifth, showing that any move from car to bus use is likely to have unequal regressive effects across countries, likely due to different mobility habits and options.

Figure 5: Expenditure on bus transport as a share of total household expenditure in Germany, France and Spain

Source: Eurostat. Note: comparison of the first and second quintiles with the average of the last three. This data refers to ‘public transport by road’ exclusively, thus not covering trains, trams or other means of public transportation. For Germany for example, this corresponds to an average of €109 annually.

3 The policy solutions available: ETS2 national revenues and the SCF

3.1 Structuring of ETS2 allowances and revenues

The estimated 5700 million ETS2 allowances that will be allocated through auctions between 2027 and 2032 will generate substantial public revenue, the total depending on the carbon price. The price ceiling that the European Commission aims to protect is €45 per tonne of CO2 in 2020 prices, corresponding approximately to €60 when the ETS2 takes effect in 2027. However, actual prices may deviate significantly 13 .

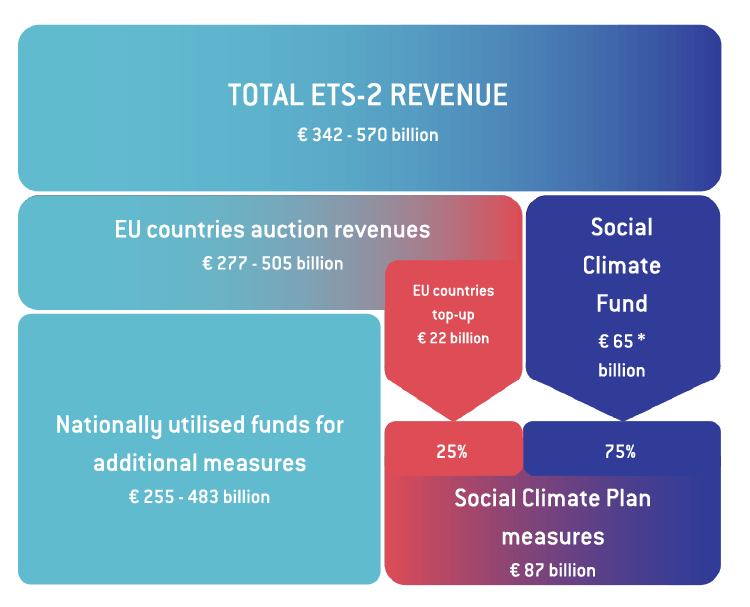

Figure 6: Flow of ETS2 revenues, 2027-2032

Source: Bruegel based on European Commission and Braungardt et al (2022). Note: the funding ranges correspond to an average CO2 per tonne price from €60 to €100 for 5700 million allowances. * In its first year, 2026, the SCF will be part financed by ETS1 revenues.

Of the total allowances, one portion will be distributed among EU countries based on their historical emissions between 2016 and 2018. This share, in conjunction with the allowance price, determines the countries’ auction revenues. The second part of the allowances will be allocated to the Social Climate Fund 14 , totalling €65 billion 15 . Countries top-up the SCF funding by nationally co-financing the measures to be implemented under Social Climate Plans (SCPs), the nationally designed spending proposals. Countries are obliged to jointly fund their SCPs and to top up their own shares for achieving the measures under their SCPs.

3.2 The importance of national revenues

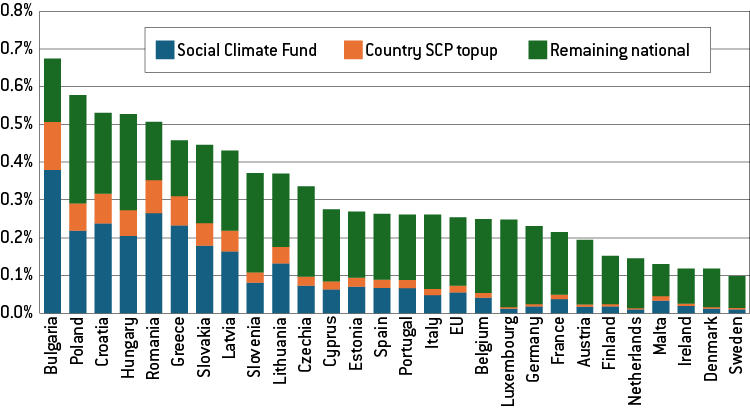

The funds flowing into national budgets come from the auctioning of allowances allocated to each EU country. This represents the largest share of total revenue, with estimates ranging between €255 billion to €483 billion in total, suggesting significant potential for national measures to tackle both emissions and distributional concerns. Figure 7 shows the expected revenues per country as percentage of GDP.

Figure 7: Annual expected ETS2 resources per EU country, % of GDP

Source: Bruegel based on EU Regulation 2023/955 and the European Environmental Agency. Note: a carbon price of €60/tCO2 is assumed.

For high-income countries, which will receive smaller shares of SCF financing, the focus will be on the efficient use of national resources. The spending of this money is less strictly regulated than the SCF. According to the regulation, measures should target vulnerable households or contribute tangibly to the reductions of emissions. However, the increased discretion for governments means that they might prioritise different political objectives, such as public support for climate policies 16 , electoral impact, jobs or support for specific constituencies, instead of addressing social issues or supporting clean investments.

3.3 The SCF: purpose and allocation

The national SCPs detailing how each country plans to spend its share of the fund must be sent to the European Commission in June 2025. For each measure, milestones and targets must be defined, with SCF payments to the countries only made after they are reached. The measures themselves must aim to alleviate the additional financial pressure ETS2 puts on vulnerable households and SMEs. Only a maximum of 37.5 percent of the total costs of the SCPs may be allocated to temporary direct income support. Finally, up to 2.5 percent may be used for improving and building capacity of implementing bodies; this can include consultations, studies or communication activities (Regulation (EU) 2023/955).

The money pooled in the SCF is distributed among countries in order to ensure the fairest outcome. The allocation formula takes into account total population, population at risk of poverty living in rural areas, the percentage of households in utility bill arrears, gross national income per capita in purchasing power standard, overall greenhouse gas emissions and CO2 emissions from fuel combustion by households. This results in the distribution seen in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Social Climate Plans expected funding 2026-2032, € billions

Source: Bruegel based on the European Commission and Eurostat.

The five greatest beneficiaries of SCF funding in absolute terms are Poland, France, Italy, Spain and Romania. However, this figure does not take into account the number of (vulnerable) households in each country (Figure 9).

Figure 9: SCF resources available per household

Source: Bruegel based on the European Commission and Eurostat.

Relative to households in need, Bulgaria and Poland will have substantial financial resources to aid households falling into the lowest 20 percent or 30 percent of the income distribution, or at least to shield them from aggravated energy and transport poverty. For higher-income countries, SCF funds will not be sufficient to alleviate the burden of even the first income decile of households, making efficient use of national revenues even more important.

4 Targeting: the biggest obstacle to implementation

4.1 The role of the SCF as instrument to shield the most vulnerable

While most of the population is not fundamentally opposed to climate policy 17 , the social justice component must be carefully calibrated to ensure public support, through fairness in burden-sharing and preventing expensive fossil fuel lock-ins (Gagnebin et al, 2019). Revenue recycling can contribute to this, while also fostering patience among those bearing the costs of the policies, allowing time for policy-driven investments to take effect and deliver tangible benefits.

However, evidence suggests that policies gain more support if the affected populations are compensated equally (Woerner et al, 2024). Lower-income groups tend to be in favour of any compensation mechanisms, whereas higher-income groups (often with more political power) may disagree with policies supporting only the most affected and favour social investment strategies (Eick et al, 2024). Political and economic systems already deprioritise the needs of the most vulnerable, mainly benefitting middle-income groups or industrial workers, with greater electoral and political significance, strengthening the need for an instrument such as the SCF.

Furthermore, from a utilitarian perspective, allocating resources to the most vulnerable improves overall welfare, as one euro has a higher marginal impact on a lower-income household than a wealthier one.

4.2 The main obstacle to implementation

Implementing effective targeting in climate policies is complex and costly, requiring significant administrative capacity that many countries lack. Striking a balance between simple measures prone to misallocation and well-targeted policies that impose a heavy bureaucratic burden is essential. Administrative capability is a significant barrier to the success of the SCF, particularly in Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, where means-tested support accounts for only 1 percent to 4 percent of total social spending, compared to 10 percent to 12 percent in Western Europe and 35 percent in Denmark (Figure 12). This limited use of means-tested support raises concerns about the ability of CEE countries to reach vulnerable groups.

Figure 10: Means-tested support across Europe, % of total social spending

Source: Bruegel.

While using existing channels, such as unemployment benefit schemes, can reduce administrative burdens, they do not cover all citizens. If means-tested targeting is not feasible, countries might favour a more universal approach using secondary criteria such as postal codes. Targeting could also be carried out ex post, for example coupling a uniform transfer with a measure such as income taxation of that payment, eg for households above a certain income threshold (in this case it must be ensured tax backflows are also only available for SCP measures). Application-based schemes can reduce data-collection efforts but risk excluding the most vulnerable, who are often the least likely to apply.

Overall, the 2.5 percent limit on use of SCF resources for building administrative capacity appears too restrictive, especially in light of the experience of the low absorption rate of another EU fund, the Just Transition Fund (Box 1). Expanding this allocation through national revenues could enhance transparency, reduce political favouritism and build infrastructure for future crises.

Box 1: the Just Transition Fund

The experience of the Just Transition Fund (JTF), intended to support EU countries that are “expected to be the most negatively impacted by the transition towards climate-neutrality,” 18 offers insights on how to implement climate policies that target specific groups. Territorial just transition plans in many countries include tailored goals, such as upskilling workers for transitions away from mining. Achieving effective targeting requires collaboration between the Commission, national and local authorities, and civil society actors such as universities and NGOs. However, absorption rates raise concerns about the capacity of countries to implement policies swiftly. By August 2024, only 1 percent of funding was spent, and just 26 percent of the budget was allocated, well below the 70 percent target set for 2026.

Figure 11: EU Just Transition Fund implementation, % of spending allocation

Source: European Commission Cohesion Open Data Platform.

If the SCF were to suffer from a similar absorption rate, vulnerable households and SMEs would be exposed to the ETS2-induced price increase without benefitting from the SCF resources for years. Given the bigger weight of the SCF over the JTF, both in terms of funding (€87 billion vs €27 billion, including national cofinancing) and coverage (all EU vs 96 territories), it is crucial that the EU and member states have in place a strong structure for policy design and implementation.

4.3 The energy crisis case

The problem of targeting was identified during the energy crisis of 2022-23. Policies rolled out during the crisis often failed to promote energy savings or target the most vulnerable energy users. Many countries resorted to universal value-added tax reductions on energy bills, electricity price caps and schemes based on past consumption expenditures. Only 27 percent of the total funding disbursed to alleviate the pressure from the energy crisis was targeted (Sgaravatti et al, 2024).

Having to quickly react to crisis because of a lack of preventative measures can cost governments huge sums without effectively alleviating the strain on the most affected parts of the population. Creating a framework that allows targeted support to reach the most vulnerable is thus not just a goal of the ETS2, but could also prove essential in a future crisis.

5 Policy suggestions to inspire countries preparing their Social Climate Plans

5.1 Taxonomy of support

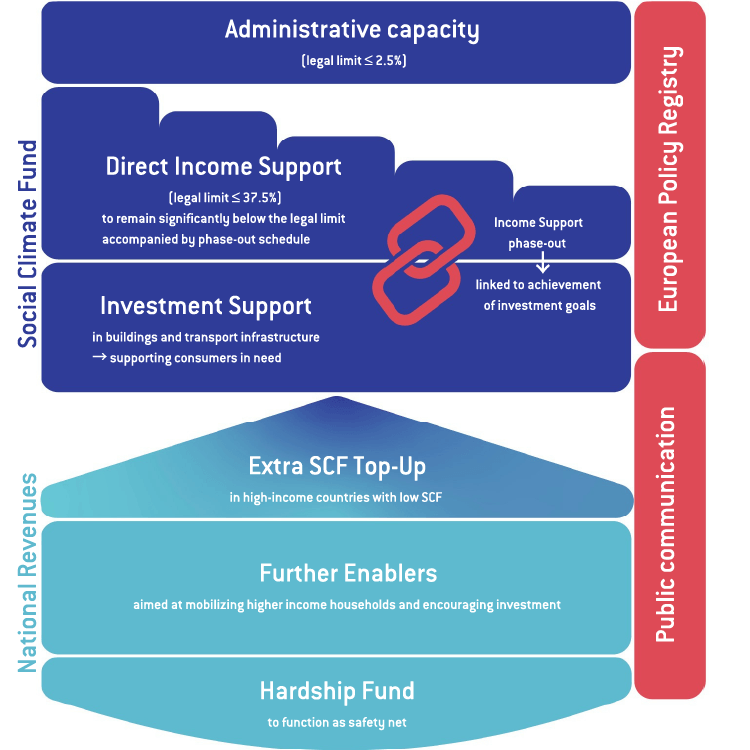

The ETS2 offers a significant opportunity to address longstanding social issues through its revenue recycling element, but its success hinges on proper structuring of this element. In Figure 12 we propose a taxonomy of support detailing the use of SCF, national revenues and additional suggestions.

Figure 12: Taxonomy of support to guide the structuring of revenue use

Source: Bruegel.

The individual elements of the taxonomy aim to contribute to the achievement of comprehensive, targeted, flexible and fair policies in EU countries. Bringing coordinated policies together and creating a system with multiple layers of support will help overcome the challenge of targeting assistance.

The European Commission has published a collection of good-practice examples and case studies (Ludden et al, 2024) that can serve as a point of reference for EU countries when deciding on suitable measures.

5.2 Transport guidelines

Direct income transfers, if used, should be tied to a household’s location and characteristics

Measures must consider the rural-urban divide. If EU countries want to employ direct income support, it should target low-income households in rural communities. This targeting hinges on the effective use and extension of administrative capacities, for example making use of tax declarations and postal codes. A clause could also be included that would allow urban commuters to request the same lump-sum payment granted to households in rural communities if they can prove commuting distance above a certain threshold, or in areas underserved by public transport.

Rural areas should focus on adoption of electric vehicle car-sharing or leasing schemes and increase incentives for fleet electrification

Investment support for car-sharing or leasing for electric vehicles, rather than expensive and regressive subsidies for vehicle purchases, is likely the most efficient option to alleviate transport poverty in rural communities. The French example of offering low-income citizens in rural communities subsidised leasing rates should be expanded across the EU, as it has proven immensely successful. The leasing scheme resulted in 50,000 households benefitting from leasing rates of €100-€150 per month for a minimum of three years 19 . By offering monthly instalments as an alternative to buying, the scheme could successfully circumvent the high upfront cost of purchasing a new electric vehicle (Ludden et al, 2024). Using some funds to support public electric-vehicle infrastructure additionally heightens the attractiveness of purchasing for the middle class, while supporting the uptake of leasing schemes for lower-income households.

Social leasing schemes may also favour cars from European manufacturers, stimulating demand for domestic production, with implications for competitiveness, as the cheapest available option to consumers are currently Chinese electric vehicles. Furthermore, as 80 percent of Europeans purchase used vehicles, schemes would assist in the creation of second-hand markets for electric vehicles, where current supply is insufficient, providing a stronger incentive for households to purchase European electric vehicles at discounted prices, helping lower-income households make this investment.

Urban centres and towns should offer discounted public transport for the most vulnerable

For urban areas, the focus should be on improving access to and the feasibility of using public services in towns and cities, offering drastically cheaper or free public transport to the poorest.

To encourage uptake of public transport options in urban areas, countries could follow the example of Brussels. Free travel within the city is granted to a variety of residents, including young children and certain groups of people reliant on social benefits. Discounted tickets are available to students and senior residents. Empirical evidence from other contexts, for example the UK, shows that usage among lowest-income beneficiaries is double that of those who are eligible but have more financial means (Ludden et al, 2024).

A scheme that introduces uniform standards and criteria, such as for modes of payment in buses (eg a free-travel card that works in buses all over the country), across regions and municipalities can also contribute to a lower total administrative cost and achieve better connectivity of citizens that otherwise might be at risk of social exclusion due to transport poverty. Beyond the social factors, free or discounted public transport may have a positive impact in terms of reducing congestion and emissions from transport. Tallinn for example noted a 9 percent increase in the share of public transport in personal mobility and a decrease of 3 percent in car usage, after abolishing fares for public transport 20 .

5.3 Buildings guidelines

Finding targeted way to lower electricity bills that circumvent the lack of administrative capacity and/or granular data

Given the poor availability of granular data on energy performance of buildings and income levels, public administrations could build composite indices using proxy metrics for energy use, such as years of construction, together with socio-economic indicators for people living in certain areas, such as unemployment benefits and crime rates. This data could give a reliable picture of where support should be targeted.

A similar approach was used by the Community Energy Savings Programme (CESP) in England to target low-income areas with energy-efficiency interventions. The areas were chosen based on an index capturing different aspects of deprivation, calculated at the neighbourhood-level linked to postal codes. The scheme was funded by an obligation on major energy suppliers and electricity generators to provide energy-efficiency measures at very low cost or for free. The cost of the energy supplier obligation was passed on by energy companies to all customers via their energy bills, keeping the impact on household bills negligible (Ludden et al, 2024). As the only eligibility criteria was the postal code, the scheme was limited in its administrative burden and reached vulnerable households that may have potentially been deterred by elaborate application processes.

Ensuring the alignment of incentives for both landlords and tenants

Landlords might be inclined to evict vulnerable households in order to refurbish houses and apartments and re-let them for higher rents (‘renovictions’). One option would be to add legal obligations to renovation schemes to protect tenants after energy-efficiency investments have been carried out. Germany put forward an initiative that incentivises landlords to carry out renovations, while guaranteeing financial support for tenants that receive basic income support. Rental increases linked to renovation costs are covered by the scheme and are paid out directly to the landlord using an existing channel, such as the local institution responsible for unemployment payments. The amount corresponds to the home’s energy efficiency rating, encouraging landlords to carry out renovations to increase their net earnings while simultaneously shielding vulnerable tenants from renovictions (Ludden et al, 2024).

Schemes must meaningfully support the energy transition of low-income households and should not lead to excessive profits for those who do not rely on support

Through application processes that use stringent criteria, the targeting of support schemes can be improved. This helps prevent support flowing towards wealthy households that do not need the funding. ‘Gent knapt op’ is a scheme in Ghent, Belgium, which focuses on improving housing quality and improving energy efficiency to reduce emissions and to support homeowners with limited means. Eligible participants must have a low income and own one home where they must be resident and which complies with specific safety conditions (eg fire insurance). The renovation is carried out and financed by Ghent’s Public Centre for Social Welfare, does not require prefinancing, and homeowners are only required to pay back the renovation cost if the renovated house is sold or rented out. Through this repayment condition, the scheme is very targeted, avoids profits falling to affluent households and achieves both objectives – improving living conditions for those who would otherwise not be able to finance it and energy improvements (Stad Gent, 2022).

Introduction of heat-pump leasing

Only 6 percent of households in the EU used heat pumps in 2021 (Cotê and Pons-Seres de Brauwer, 2023), with heat pump sales slowing in recent years (EHPA, 2024). This number could be significantly increased via a leasing scheme that lowers the cost barrier. Most households would like to adopt lower emissions heating systems but are hindered by high prices paired with technical and operational concerns. This is especially the case in markets where heat pumps are in the early stages of being rolled out. A government-supported leasing system could push take up by removing these barriers through flexible packages that include maintenance and repairs and/or offer a lease-to-own option. Finally, to further support low-income households, a scheme could be set up whereby monthly lease payments can (partially) be deducted for tax purposes (Cotê and Pons-Seres de Brauwer, 2023).

5.4 Beyond the SCF: putting national revenues to good use

SCF top-up

For higher-income countries, the SCF will likely be insufficient to shield low-income households fully from the ETS2 impact on energy prices, while simultaneously supporting vulnerable households and SMEs in making the required green investments (Braungardt et al, 2022) 21 . It is therefore recommended that in these countries, the national top-up of their social climate plans funding is above 25 percent, especially if the ETS2 carbon price goes above the Commission’s soft cap. As national revenues are less strictly regulated than funds allocated to the SCF, this ensures that funds would reach the groups that rely on them most, rather than allowing governments a simple solution with measures that could lead to policies that benefit politically important households more than vulnerable ones.

Additional enablers to mobilise the middle class

Given the importance of electricity in buildings and transport, another focus should be the rebalancing of energy prices in favour of electricity. One option would be to design contracts for difference for electric heating (McWilliams and Zachmann, 2021). These would represent a form of insurance for consumers so that when they invest in fuel-switching (for example, by installing an electric heat pump), they are guaranteed that the price of operating the clean appliance will always be cheaper than the displaced fossil-based one. For example, a strike price of €100 per tonne of CO2 would ensure the investment case for fuel switching away from fossil-based heating appliances in virtually all EU countries.

Governments should also encourage the emergence of smart electricity tariffs, which allow heat-pump users to adjust their electricity usage based on the wholesale electricity price, thermal features of the house and efficiency changes due to varying outdoor temperatures. This could further increase both energy and cost savings for consumers, as seen in Scandinavian countries (Burger, 2024). Similarly, the deployment of vehicle-to-grid technologies and dynamic tariffs can enable users of electric vehicles to gain money by feeding electricity into the grid in periods of high electricity prices. This is already happening in Norway, where consumers can earn €70-€100 per year by enabling smart charging of their electric vehicles, on top of any potential cost savings from dynamic tariffs (Rangelova et al, 2024).

Hardship relief fund

Even if the outlined measures succeed overall, some households will likely fall through the cracks, with their vulnerabilities unaddressed. While a top-up linked to carbon price increases can extend SCP schemes, an additional ‘hardship fund’ might be needed for special cases when existing support fails. Access criteria should be country-specific, identifying gaps left by SCP measures. For example, if public transport support is postal-code based, urban residents commuting to rural areas might be excluded despite their vulnerability – precisely when a hardship fund should intervene.

Evidence from the energy crisis shows that uptake of such funds remains low if they are too obscure or complex 22 . A collaborative approach involving energy providers could help, using energy usage data 23 to identify at-risk households through indicators such as low consumption, unpaid bills or heating type. These households could then receive tailored guidance, simplifying the process for potential applicants, increasing the fund’s visibility and providing valuable data for future crises.

5.5 General recommendations

Coupling of income and investment support

As the SCF is foreseen as an instrument to aid vulnerable households in their transitions, monetary benefits should be slowly phased out or transformed to target the source of the vulnerability rather than treating its symptoms. If such a phase-out schedule is implemented, it needs to be clearly communicated and tied to the achievement of investment support targets, to ensure a smooth transition in which households still reliant on support are not left behind. This could be coupled with the hardship relief fund: in the later ETS2 implementation stages, this instrument will remain as support layer for the most vulnerable, while more general income support is phased out at an earlier point.

Fossil-fuel subsidy phase-out

The move away from fossil fuels would be jeopardised by the continuation of fossil-fuel subsidies, which can actively work against the decarbonisation mechanisms of carbon pricing by undermining its price signal. Fossil-fuel subsidies also prevent investments in renewable energy, building renovation and electrified transport 24 . In the EU, subsidies were introduced to shield households from rising costs during the energy crisis, these widely untargeted subsidies are outdated. Currently, only around half of EU countries have put forward concrete plans detailing how they will phase out fossil-fuel subsidies (Nill, 2024). However, the ETS2 and its revenues could alleviate households’ financial burdens to a similar extent to fossil-fuel subsidies, if implemented correctly, while aligning with climate goals.

European registry of policies

To capture characteristics of individual policies, the design and implementation of the SCPs should be accompanied by the establishment of a ‘European registry of policies’. This would serve as a centralised resource, cataloguing characteristics of various individual policies implemented by EU countries, including their benefits, limitations and targeting approaches. Regular updates would ensure the registry reflects lessons learned in real time. It would act as a dynamic knowledge-sharing platform, enabling EU countries to explore proven strategies and innovative ideas from others, fostering cross-country learning.

By providing access to diverse approaches and outcomes, the registry would help member states better exploit the inherent flexibility of the SCPs. Moreover, this initiative would encourage governments to view the preparation and implementation of SCPs as an iterative and evolving process, optimising policy effectiveness and alignment with national priorities.

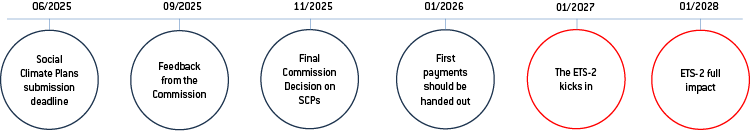

Ensure proper sequencing and timing, social outreach and communication

As the SCF is scheduled to start in 2026, national governments need to prepare support measures that will be accessible to households by this time. Initial support should be rolled out before the price effects of the ETS2 are felt by citizens. For this purpose, a communication channel should be set up to communicate ETS2’s impact, when it will materialise and how to access support.

Figure 13: ETS2 and SCF Timeline

Source: Bruegel.

Generally, making information about the scheme and spending of revenues readily available can aid in increasing support among the general public – especially if this communication happens before consumers feel the price increases.

Governments should analyse the needs of their populations, assess their ability to provide effective support and continuously seek to improve their approach. Poorly designed plans risk misallocating billions of euros, failing to protect the most vulnerable. A well-structured, transparent, and timely approach is essential to ensuring that the SCF delivers on its promise of turning climate action into a just and inclusive transition, rather than an economic burden.

References

Agora Energiewende and Agora Verkehrswende (2023) Der CO2-Preis Für Gebäude Und Verkehr. Ein Konzept Für Den Übergang Vom Nationalen Zum EU-Emissionshandel, Agora Energiewende, available at https://www.agora-energiewende.de/fileadmin/Projekte/2023/2023-26_DE_BEH_ETS_II/A-EW_311_BEH_ETS_II_WEB.pdf

Ahrendt D., H. Dubois, V. Ezratty, T. Fox, J.M. Jungblut, A. Pittini … J. Vandamme (2016) Inadequate housing in Europe: Costs and consequences, Eurofound, available at https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2016/inadequate-housing-europe-costs-and-consequences

Braungardt, S., K. Schumacher, D. Ritter, K. Hünecke and Z. Philipps (2022) The Social Climate Fund – Opportunities and Challenges for the buildings sector, Öko-Institut e.V., available at https://www.oeko.de/en/publications/the-social-climate-fund-opportunities-and-challenges-for-the-buildings-sector/

Burger, J. (2024) Imagine all the people. Strong growth in tariffs and services for demand-side flexibility in Europe, Regulatory Assistance Project, available at https://www.raponline.org/toolkit/strong-growth-in-tariffs-and-services-for-demand-side-flexibility-in-europe/

Castle, C., Y. Hemmerlé, G. Sarcina, E. Sunel, F. Maria D’Arcangelo, T. Kruse … M. Pisu (2023) ‘Aiming better: government support for households and firms during the energy crisis’, OECD Economic Policy Paper No. 32, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, available at https://doi.org/10.1787/839e3ae1-en

Cotê, E. and C. Pons-Seres de Brauwer (2023) ‘Preferences of homeowners for heat-pump leasing: Evidence from a choice experiment in France, Germany, and Switzerland’, Energy Policy 183: 113779, available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113779

Duma, D., C. Postoiu and M. Cătuți (2022) The Impact of the Proposed EU ETS 2 and the Social Climate Fund on Emissions and Welfare: Evidence from the Literature and a New Simulation Model, Energy Policy Group, available at https://www.euki.de/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/ETS2_Policy_Brief_EPG-1-1.pdf

Eden, A., I. Holovko, J. Cludius, N. Unger, V. Noka, K. Schumacher … K. Głowacki (2023) Putting the ETS 2 and Social Climate Fund to Work - Impacts Considerations, and Opportunities for European Member States, Policy Report, adelphi, Öko-Institut, Center for the Study of Democracy and WiseEuropa, available at https://adelphi.de/system/files/document/policy-report_putting-the-ets-2-and-social-climate-fund-to-work_final_02.pdf

Eick G.M., B. Burgoon and M.R. Busemeyer (2023) ‘Public preferences for social investment versus compensation policies in Social Europe’, Journal of European Social Policy 33(5): 555-569, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/09589287231212784

EHPA (2024) European Heat Pump Market and Statistics Report, European Heat Pump Association, available at https://www.ehpa.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Executive-summary_EHPA-heat-pump-market-and-statistic-report-2024-2.pdf

Gagnebin, M., P. Graichen and T. Lenck (2019) ‘The French CO2 Pricing Policy: Learning from the Yellow Vests Protests’, Background, Agora Energiewende, available at https://www.agora-energiewende.org/fileadmin/Projekte/2018/CO2-Steuer_FR-DE_Paper/Agora-Energiewende_Paper_CO2_Steuer_EN.pdf

GBPN (2013) What Is A Deep Renovation Definition?, Technical Report, Global Building Performance Network, available at https://www.gbpn.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/08.DR_TechRep.low_.pdf

Gevorgian, A., S. Pezzutto, S. Zambotti, S. Croce, U.F. Oberegger, R. Lollini, L. Kranzl, and A. Müller (2021) European Building Stock Analysis: a country by country descriptive and comparative analysis of the energy performance of buildings, Eurac, available at https://webassets.eurac.edu/31538/1643788710-ebsa_web_2.pdf

Graichen, J. and S. Ludig (2024) Supply and Demand in the ETS 2: Assessment of the new EU ETS for road transport, buildings and other sectors, Interim Report, German Environment Agency, available at https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/11850/publikationen/09_2024_cc_ets_2_supply_and_demand.pdf

Günther, C., M. Pahle, K. Govorukha, S. Osorio and T. Fotiou (2024) ‘Carbon prices on the rise? Shedding light on the emerging EU ETS 2’, mimeo, available at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4808605

Held, B., C. Leisinger and M. Runkel (2022) Assessment of the EU Commission’s Proposal on an EU ETS for buildings & road transport (EU ETS 2): criteria for an effective and socially just EU ETS 2, Report 1/2022, Klima-Allianz Deutschland, Germanwatch, WWF Deutschland, CAN-Europe, available at https://www.wwf.de/fileadmin/fm-wwf/Publikationen-PDF/Klima/Criteria-for-an-effective-and-socially-just-EU-ETS-2.pdf

Keliauskaitė, U., B. McWilliams, G. Sgaravatti and S. Tagliapietra (2024) ‘How to Finance the European Union’s Building Decarbonisation Plan’, Policy Brief 12/24, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/how-finance-european-unions-building-decarbonisation-plan

Kiss M. (2022) ‘Understanding transport poverty’, At a Glance, October, European Parliamentary Research Service, October, available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2022/738181/EPRS_ATA(2022)738181_EN.pdf

Linden J., C. O’Donoghue and D.M. Sologon (2024) ‘The many faces of carbon tax regressivity—Why carbon taxes are not always regressive for the same reason’, Energy Policy 192: 114210, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2024.114210

Ludden V., A.M. Laine, F. Vondung, T. Koska, F. Suerkemper, H.Thomson and B. Houillon (2024) Support for the implementation of the Social Climate Fund: note on good practices for cost-effective measures and investments, European Commission: Directorate-General for Climate Action, Ramboll Management Consulting, Wuppertal Institute for Climate Environment and Energy, available at https://op.europa.eu/s/z0Vp

McWilliams, B. and G. Zachmann (2021) ‘Making sure green household investment pays off’, Analysis, 19 July, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/making-sure-green-household-investment-pays

Menner M., G. Reichert, J.S. Voßwinkel and A. Wolf (2025) Towards Decarbonised Road Transport Driven by a Globally Competitive EU Automotive Industry, cepStudy, Centres for European Policy Network, available at https://www.cep.eu/eu-topics/details/towards-decarbonised-road-transport-driven-by-a-globally-competitive-eu-automotive-industry.html

Pisani-Ferry, J. and S. Mahfouz (2023) The Economic Implications of Climate Action, Report to the French Prime Minister, France Stratégie, available at https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/files/files/Publications/English%20Articles/Les%20incidences%20%C3%A9conomiques%20de%20l%E2%80%99action%20pour%20le%20climat/2023-the_economic_implications_of_climate_action-report_08nov-15h-couv.pdf

Rangelova, K., B. Petrovich, D. Jones and C. Bruce-Lockhart (2024) Clean flexibility is the brain managing the clean power system, EMBER, available at https://ember-energy.org/app/uploads/2024/10/Clean-flexibility-is-the-brain-managing-the-clean-power-system.pdf

Sgaravatti, G., S. Tagliapietra and C. Trasi (2024) ‘Europe’s fiscal policy response to the energy crisis: lessons learned for a greener way out’, Energy Efficiency 17(90), available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-024-10275-0

Stad Gent (2022) Gent knapt op, available at https://stad.gent/sites/default/files/media/documents/22_00589_Minimagazine_Gent%20Knapt%20OP_web_0.pdf

Strambo, C., M. Xylia, E. Dawkins and T. Suljada (2022) The Impact of the EU Emissions Trading System on households: how Can the Social Climate fund support a just transition? Stockholm Environment Institute, available at https://doi.org/10.51414/sei2022.024

Wier, M., K. Birr-Pedersen, H. Klinge Jacobsen and J. Klok (2005) ‘Are CO2 taxes regressive? Evidence from the Danish experience’, Ecological Economics 52(2), available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.08.005

Woerner,A., T. Imai, D.D. Pace and K.M. Schmidt (2024) ‘How to increase public support for carbon pricing with revenue recycling’, Nature Sustainability 7: 1633–1641, available at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-024-01466-9

Zachmann, G., G. Fredriksson, and G. Claeys (2018) The Distributional Effects Of Climate Policies, Blueprint 28, Bruegel, available at https://www.bruegel.org/book/distributional-effects-climate-policies

댓글

댓글 쓰기