Geopolitical conflict impedes climate change mitigation

Introduction

During the 27th Conference of the Parties (COP) in Egypt, the Secretary-General of the United Nations António Guterres appealed to the world community to work together or face “climate hell”1. In his speech, Guterres hinted at conflicts posing barriers to cooperation on climate issues: “The war in Ukraine, other conflicts, […] have had dramatic impacts all over the world. But we cannot accept that our attention is not focused on climate change”1. Indeed, contrary to the hopes for a world society and for the end of history2 after the end of the Cold War, geopolitical fragmentation and conflicts have been spreading, and have rendered international consensus on how to escape Guterres’ climate hell more challenging and—as time passes—more unlikely.The developments leading to the current geopolitical fragmentation have not occurred overnight, but were foreseeable for some time. Nevertheless, Guterres’ concern about how conflicts and socio-economic disruptions in the fabric of global relations are significantly decelerating climate change mitigation has so far not been heeded, neither in the Assessment Reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) nor in the wider peer-reviewed literature.

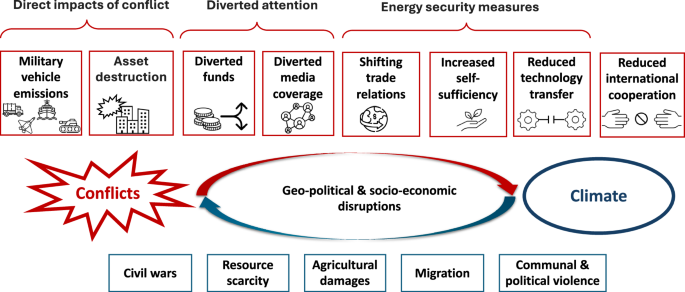

There is ample debate and publication on climate change causing conflict. Research on environmental conflicts increased since the 1990s3 and cumulated in a scientific discourse concerning conflict as a consequence of climate change, in other words, a Climate=>Conflict-nexus4 (Fig. 1, blue arrow and boxes). The question of a possible impact of climate change on conflict is discussed for direct and indirect conflictual outcomes such as wars, communal violence and the individual acceptance of and participation in political violence, but also via climate-affected conflict drivers such as resource scarcity, agricultural damages and climate-induced migration5,6,7,8 (see also Appendix 1 - The Climate=>Conflict-Nexus). While critics emphasize a lack of evidential validity for the existence of this nexus9,10, there is evidence that climate change impacts conflicts indirectly by aggravating other drivers of conflict11,12. As a result of being criticized for lacking research on a nexus between climate and conflict13, the IPCC in its 5th Assessment Report (AR5) included a chapter on Human Security14, in which, again, research on conflict as a consequence of climate change is summarized. In AR5 climate change is perceived as a threat for human security13, not just in forms of direct effects but also as unintended side effects15. The discussion on climate change causing conflict is continued in the 6th Assessment Report16. It also appears as one component in a set of global polycrises17.

On the contrary, a Conflict→Climate-nexus, i.e. the detrimental impact of conflict on mitigation (Fig. 1, red arrow and boxes), has not been systematically charted anywhere. Only in the Shared Socio-Economic Pathway (SSP) 3, which represents the worst case of projected SSPs in AR6, a conflict-prone geo-political situation is vaguely defined as a “Rocky Road”18: “A resurgent nationalism, concerns about competitiveness and security, and regional conflicts push countries to increasingly focus on domestic or, at most, regional issues. Policies shift over time to become increasingly oriented toward national and regional security issues. […] A low international priority for addressing environmental concerns leads to strong environmental degradation in some regions.”19,20. Although implicitly indicated, geopolitical conflicts play no explicit role in the future projection of the Rocky Road in Integrated Assessment Models (see also Appendix 2—The role of conflict in the SSPs). Conflicts also do not feature in the examination by Fujimori et al.20 of whether the SSP narratives are coherent. SSPs were developed to describe socio-economic trends at the level of the world or large world regions21. SSP3 recognises that more regional rivalries lead to less international cooperation and de-globalisation. However, it cannot recognise that geopolitical rivalries such as conflicts lead to shifts in the geopolitical balance of power, e.g. between the global North and South, and shift international cooperation patterns in terms of re-globalisation, e.g. the expansion of the BRICS-alliance, which has an impact on global mitigation policy. The consideration of such ‘surprise scenarios’22 is discussed, as is the extension and enhancement23 of SSPs. Geopolitical conflicts, such as those we outline, continue to play a subordinate role. Thus, the Conflict=>Climate-nexus constitutes an under-theorised research direction.

Not considering the Conflict=>Climate-nexus in IPCC ARs is significant and consequential: For more than 30 years, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has provided scenarios that depict options for mitigating climate change. The IPCC’s focus is primarily on the technological pathways required to achieve reductions of greenhouse gas emissions. In their omission of conflicts impeding mitigation, IPCC scenarios are likely overly optimistic. Moreover, increasing global fragmentation and conflict, exemplified by the Ukraine and Gaza wars and struggles for global political and economic hegemony, mean that mitigation will likely be even more obstructed in the future. Therefore, the speed of planned mitigation may need to be even faster than reflected in today’s mitigation targets, because we need to consider that global conflicts cause significant disruptions that will lead to delays in the transition to net zero.

Evidence for the Conflict→Climate link

Here we aim to elucidate the adverse effects of conflict on climate change. Our understanding of conflict follows the Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research, which defines conflict as “… the clashing of interests (positional differences) on national values of some duration and magnitude between at least two parties (organized groups, states, groups of states, organizations) that are determined to pursue their interests and win their cases.”24 This definition shows “conflict” understood in a general sense as covering armed, economic, trade and political clashes. Our distinction lies less in whether a conflict is armed or not, but rather in whether its effects on mitigation are direct or indirect.

Through a comprehensive survey of the (mostly grey) literature, we identify seven primary channels within the Conflict→Climate nexus (Table 1): 1) direct impacts of conflict such as military vehicle emissions, asset destruction and other impacts stemming from war (such as damage to fuel infrastructure and reconstruction activities), 2) diverted attention, such as funds or media coverage, 3) energy security measures such as shifting trade relations, increased self-sufficiency, and reduced technology transfer, and 4) reduced international cooperation. We arrived at this typology by considering the causal mechanisms underlying the various channels. First, we made a clear distinction between direct and indirect effects, that is channels involving actual greenhouse gas emissions, such as military vehicle emissions and direct war-related impact, and channels where effects are not caused by the actual warfare. Diverted attention includes the reassignment of budget allocations from climate change mitigation to military purposes, or the shifting of media attention from climate change to war. Shifting trade relations, increased self-sufficiency, and reduced technology transfers affect emissions in as much as they arise out of energy security needs and alter energy markets. Reduced international cooperation focuses on the global governance aspect of climate change mitigation, distinct from trade relations or technology investment. We excluded channels that primarily affect adaptation rather than mitigation, since these do not directly cause climate change. The following paragraphs offer a summary substantiation of each of the seven channels; a more detailed version can be found in Appendix 3 - The Conflict→Climate-Nexus.

댓글

댓글 쓰기