Climate change made LA fires far more likely, study says

Human-caused climate change made the Los Angeles-area fires more likely and more destructive, according to a study out Tuesday.

Why it matters: The study — from an international group of 32 climate researchers — shows how climate change fits into the myriad factors that made the multiple blazes one of California's most destructive and expensive wildfire disasters on record.

- "Overall the paper finds that climate change has made the Los Angeles fires more likely despite some statistical uncertainty," said Gabi Hegerl, a climate scientist at the University of Edinburgh who wasn't involved in the study, in a statement.

Zoom in: In making their conclusions, World Weather Attribution researchers zeroed in on the high winds; weather whiplash from unusually wet to extremely dry conditions preceding the fires; and long-term trends.

- The scientists found that low rainfall from October through December is now more than twice as likely compared to the climate that existed before humans began burning fossil fuels such as oil, coal and gas for energy.

- But they didn't conclusively tie this to climate change.

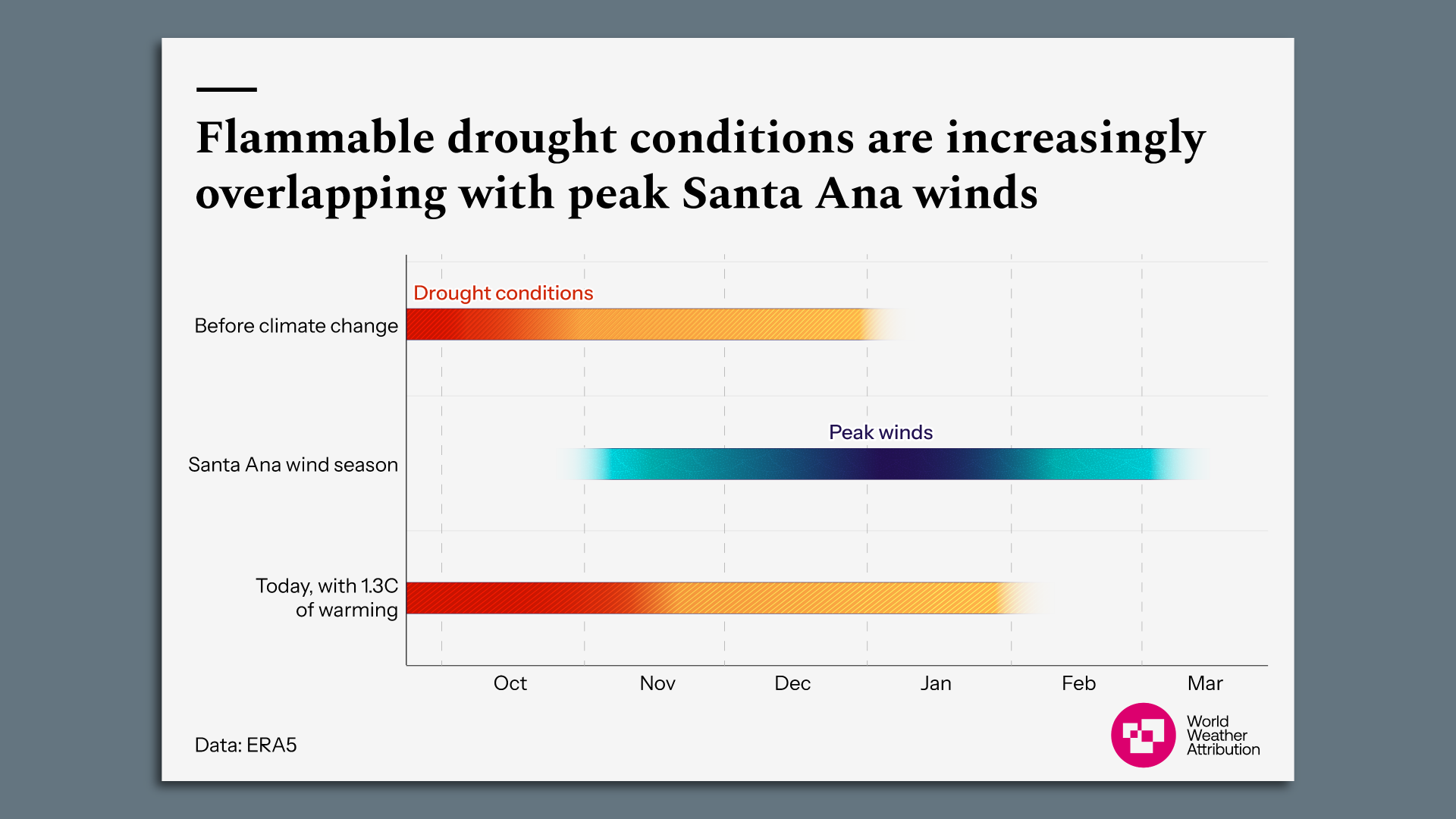

They also concluded that the LA fire season is becoming longer, with "highly flammable drought conditions" lasting about 23 more days now than during the preindustrial era.

- This makes for greater overlap between warm and dry conditions and strong Santa Ana offshore winds that can cause fires to spread quickly.

Zoom out: The study isn't the last word on this topic, nor does it come without uncertainties. But its findings are in line with other research.

By the numbers: According to the study, the hot, dry and windy conditions that propelled the flames into communities such as Altadena and Pacific Palisades were about 35%, or 1.35 times, more likely today due to the warming from burning fossil fuels such as oil, gas and coal, when compared to the preindustrial climate.

- These conditions, as measured by the Fire Weather Index, would become another 35%, or 1.8 times, more likely to occur in January if global warming reaches 2.6°C (4.68°F) above preindustrial levels.

- This amount of warming is a lower bound for what is expected by the end of the century, as the world is currently on course for upwards of 3°C (5.4°F) of warming.

- The Fire Weather Index takes multiple factors into account, including temperature, humidity, wind speed and the amount of preceding precipitation.

What they're saying: "Climate change set the stage, helping turn the hills around LA tinder-dry," said Roop Singh of the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre in a statement.

- "However, hurricane-force Santa Ana winds, the rapid spread of fires into urban zones, and a strained water system all made the blazes extremely difficult to contain," he said.

The intrigue: Climate change is also at least doubling the chances for below-average October through December rainfall in the LA area, the researchers found,

- In addition, hotter air temperatures are also making the atmosphere more efficient at evaporating moisture from the Earth's surface.

- Plants dry out faster in hotter temperatures, causing them to burn more easily.

- The study found a greater chance that drier, more combustible conditions will now overlap with the peak Santa Ana wind season in December and January.

Yes, but: The study based the rainfall trend analysis on both observational data and climate models. The models didn't show clear trends in rainfall or the fire season's end date — while the observational data did, and other published studies have as well.

- This study, like the dozens of other climate attribution studies that come soon after an extreme weather event, has yet to undergo peer review but is based on proven methods.

How they did it: The researchers used peer-reviewed methods to examine how fire events and risk in Southern California have changed since the preindustrial era.

- They conducted multiple analyses with observations and computer models.

They noted recent research showing that "hydroclimate whiplash" from very wet to drought conditions enables and worsens such wildfire events.

- In addition to this study's methods, the authors took into account peer-reviewed literature showing an increasing risk of wildfires and uptick in the extent of burned land, including in the West and Southwest, as the world warms.

Between the lines: The study notes that El Niño and La Niña, two natural climate cycles in the tropical Pacific Ocean, influence Southern California's seasonal precipitation.

The bottom line: "This is a carefully researched result that should be taken seriously," Hegerl said.

댓글

댓글 쓰기